étant un vecteur constant :

étant un vecteur constant :

L'intégration du produit vectoriel est immédiate,

le moment cinétique  étant un vecteur constant :

étant un vecteur constant :

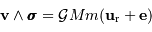

s'intègre en

s'intègre en  .

.

Intégration du 2e membre :

s'intègre en

s'intègre en

.

.

Et il ne faut pas oublier la constante d'intégration, vectorielle, ici dénommée

:

:

Le vecteur  est perpendiculaire au vecteur moment cinétique, donc dans le plan de la trajectoire.

est perpendiculaire au vecteur moment cinétique, donc dans le plan de la trajectoire.